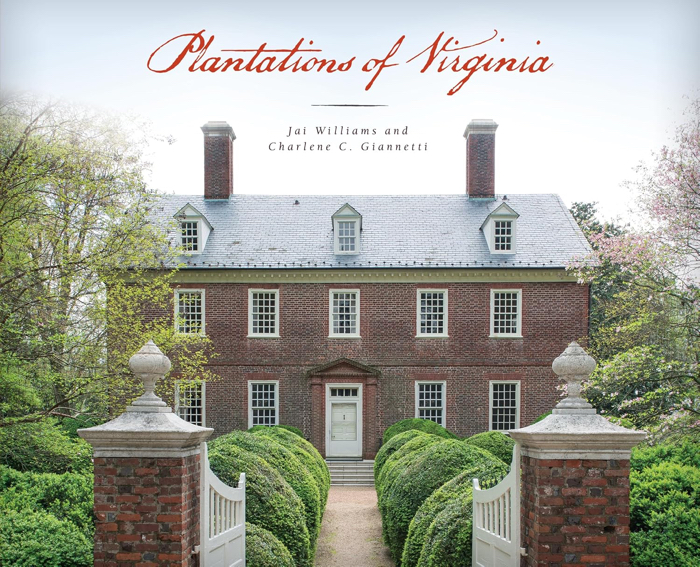

For ten years, through three Presidential administrations, I lived in Alexandria, Virginia, a suburb of Washington, D.C. Even though I had lived in our nation’s capital in the 1970s, I had never lived in Virginia, so began to explore the state. When I was offered the opportunity to write a book focusing on Virginia’s plantations, I saw that project as a way to learn more about the Old Dominion, a state that has produced eight presidents.

My co-author, Jai Williams, a talented writer and photographer, was really the driving force behind the book. As a young Black woman, she wanted to show another side of plantations, what life was like for the slaves who lived in those mansions. We spent six months traveling around Virginia, taking tours, talking with those tasked with caring for these properties. It was an eye-opening experience for both of us.

The book, Plantations of Virginia, was published by Globe Pequot in 2017. It seemed like good timing. The Black Lives Matter movement, which began in Oakland, California, in 2013, in response to the killings of Trayvon Martin, Michael Brown, and others, continued to grow. That activism about Black history accelerated the work of many plantation officials who were attempting to include the experiences of the slaves into their stories.

Leading the way were the three best known plantations: George Washington’s Mount Vernon, Thomas Jefferson’s Monticello, and James Madison’s Montpelier. These three presidents and Founding Fathers were slave owners, and, with a renewed focus on slavery, their legacies often came under attack. To their credit, those managing these historic sites dealt with the issues head on. The tours led by knowledgeable academics, some of them Black, didn’t whitewash what it was like for slaves forced into servitude.

Some of the things we learned and wrote about in the book:

In 1780, Pennsylvania’s Act for the Gradual Abolition of Slavery said that a slave living in that state for six months would become free. To prevent that from happening, George and Martha Washington, who were at that time living in Philadelphia, had their slaves sent back to Mount Vernon before the end of those six months. The Mount Vernon website recognizes the struggles of these slaves, including the biographies of many who worked on the plantation.

At any given time, 130 slaves worked at Jefferson’s Monticello. Philosophically, Jefferson didn’t like the practice of slavery, but practically he thought it was necessary for the young country to succeed. The Monticello website includes many details outlining how slavery contributed to the plantation’s history.

The Marquis de Lafayette, a great friend of Madison, was also an ardent abolitionist. Many believe that the American Revolution would not have been won without his help. He thought the new country would be based on freedom and equality and was disappointed that the Founding Fathers, including Madison, owned slaves. Madison agreed with Lafayette, but never freed slaves during his lifetime. That fact is stressed during tours of Montpelier, especially in a mock-up of the dining room with cutout figures representing those who gathered at the Madison table, including Lafayette.

We found that many of the small plantations were committed to transparency on slavery. Some had exhibits on their slave history and encouraged visitors to submit information that might help them uncover their family histories.

Of course, not all the plantations were so forthcoming. On more than one tour, the guides, usually volunteers, would emphasize that these plantation owners treated their slaves “like members of their families.” We were always surprised at the nodding heads that seemed to agree with this scenario. No matter how kind some owners were, slaves were still unpaid labor, forced to work long hours, suffered beatings and the women, rape, at the hands of overseers, and most were separated from their own families.

We ran into resistance at some plantations that were still family-owned and tightly controlled the narrative about their histories. Because we pledged to tell the truth, not create “alternate facts,” we never promised to omit negative information. Faced with not being included in the book, many relented. Those that didn’t were left out.

History is not always pretty. Slavery was a dark time in America’s past, but efforts to seriously alter those experiences will not change what happened. Attempts to rewrite or even obliterate anything about slavery in museums, universities, and other institutions, is an affront to all those whose family history will be erased. We can’t let that happen.

The Plantations of Virginia

Jai Williams

Charlene Giannetti

Top Bigstock photo: George Washington’s Mount Vernon