Eleena Ivanova Diakonova (1894-1982) was wild and outrageously opinionated. Sent to a Swiss sanatorium for tuberculosis she met poet Paul Éluard and pronounced him a “very great writer.” They were both 17. He gave her the nickname “Gala.” When Paul reached 21, the besotted couple were allowed to marry. Gala moved into his family house in Paris only to discover he’d been sent to the front. On one of his leaves, the young woman got pregnant with what would be her only child, immediately turning the (detested) baby over to her mother-in-law.

After the war, Paul went to work in the family real estate business. Gala sewed her own clothes and decorated a small apartment. More educated and cultured, she took him in hand, meeting André Breton and Louis Aragon, editors of Paris’s most prestigious literary magazine. “Being a poet was like being a rock star today,” writes Michèle Gerber Klein in Surreal- The Extraordinary Life of Gala Dali.

Paul Éluard, 1911 (Public Domain)

In 1918, Tristam Tzara invented the term Dada (hobby horse in French) which rejected logic, reason, hypocrisy, and aestheticism. Paul contributed to the movement magazine befriending artists Picabia, Marcel Duchamp, and Hans Arp. “It was a men’s club, really,” writes Klein. “Others found Gala puzzling and inconvenient.”

With what little money they had, Gala began to collect early art from Georges Braque, Juan Gris, and Giorgio de Chirico. In 1921, Max Ernst had his first one man Paris show of collage compositions. He was forbidden to leave Germany. Intrigued, the Éluards visited him.

Max’s marriage was on the rocks. His wife, Louise, remembered Gala as “…this floating, glowing creature with dark curls, crooked sparking eyes and limbs like a panther.” It was a coup de foudre = love/lust at first sight. Max spent the next summer with Gala and Paul, then moved to Paris with false papers. They became a ménage a trios. “Love has no wings/Neither does despair,” Paul wrote.

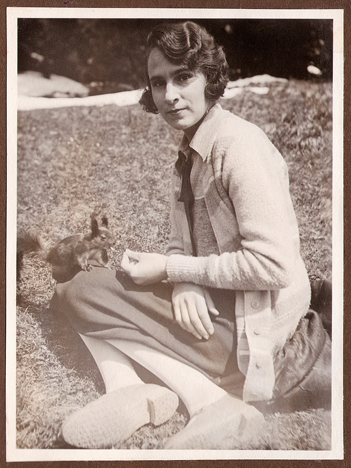

Gala playing with a squirrel, 1925 (Photo by Man Ray)

Just as Gala inspired Paul, she was now often a model for Max. Her husband became jealous and literally disappeared…with every franc in his family’s safe. When a letter finally came – from Panama City – it professed undying love. Meanwhile, Gala pressed Max to design scarves and ties which she sold, first signs of marketing acumen that would eventually raise Dali’s profile.

When Paul returned, life became a rondo of first one man and then the other. The final collaboration by all three was an 18 page poem in homage to Gala. The Surrealist Manifesto, advocating fantasy and intuition, reliance on accident and chance, supplanted Dadist attacks on formal artistic conventions. Having inherited, Paul was able to pursue new genres without having to earn money. He began to seriously indulge in debauchery. There was a period when her husband handpicked Gala’s lovers.

That April, 24 year-old Salvador Dali arrived from Catalonia. (Breton mentored him.) “He was spoiled, tantrum prone, and would have turned Little Lord Fauntleroy’s head,” writes Klein. Once again, it was love at first sight. Dali pursued the married Gala with the focus of a stealth missile. Both described as having nervous disorder, they became confidantes. Paul went back to Paris convinced the two were just friends.

Opening of the Max Ernst exhibition at the gallery Au Sans Pareil, 1921. From left to right: René Hilsum, Benjamin Péret, Serge Charchoune, Philippe Soupault, on top of the ladder with a bicycle under his arm, Jacques Rigaut (upside down), André Breton and Simone Kahn (Public Domain)

Dali painted 51 year-old “Galarina” without make-up in an unbuttoned, plaid oxford shirt with left breast defiantly exposed. It would be the first of many portraits. That year he would also paint “The Persistence of Memory” – his famous melting watches. In the early 1930s, the artist started to sign paintings with his and her name. “It is mostly with your blood, Gala, that I paint my pictures,” said Dali.

After Gala’s divorce, the Dalis married in a civil ceremony. Her husband developed his signature mustaches and the habit of carrying elaborate canes. He charmed, amused and provoked while she played the straight man. She was “wife, tigress, lover, mother, fashion influencer, art world royalty, model, critic, muse, collaborator, dealer, licensing manager, negotiator, hostess, bill collector, nurse, and recurring mystical centerpiece of her husband’s work,” writes Klein. The couple married in 1934.

In New York, he was feted at The Huntington Hartford (now The Museum of Art and Design). “L’Age d’Or,” a satirical comedy film directed by Luis Buñuel was shown at MOMA. (It was Dali’s second film of four. Buñuel was jealous of Gala.) The couple moved into a mostly unfurnished flat. Prince Jean-Louis de Faucigny-Lucinge arranged that 12 patrons would each be responsible for a month of the Dali’s expenses in exchange for art.

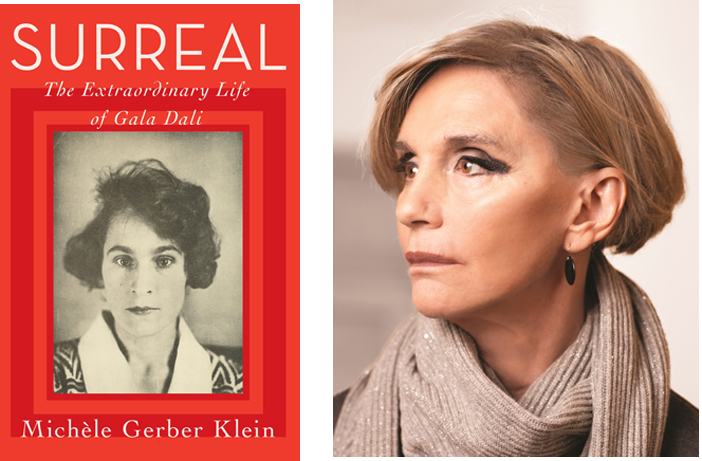

Right: Michèle Gerber Klein (Justine Cooper Photography)

The New York Times called Dali’s work, “putting Freudian Themes on canvas.” Gala became his manager. Julian Levy, who represented her husband wrote that before Gala, Dali was “a half timid, half malicious outsider in a threadbare overcoat…” Patron Edward James (enamored of Gala) took over from the Prince. Because of his wife, Dali never had trouble paying their often exorbitant bills.

The artist created a stained glass clock that ticked off days not hours, upside-down stiletto and lobster hats (Gala modeled) – the latter became the receiver of a working telephone (ten were commissioned).

He wrote a novel and an autobiography. (The latter is a good read.) Success got him expelled from the Surrealists.

Gala was getting on. Still, at 77, she lunched with Max Ernst’s son and asked him back to her hotel room. He bolted. Levy said, “You should have gone with her. You don’t know what you missed.” The Dalis had a great deal of money. In later life, he escorted a good looking young blonde, Gala found herself a young man. Still they professed deep love and admiration for one another.

Dali and Gala 1942 by Philippe Halsman. “On his wife’s forehead Salvador Dali paints the head of Medusa, one of the three snaky-haired Gordon sisters whose glance turned into stone everything on which it rested.”

Andy Warhol met her at 90 and compared Gala to Greta Garbo in her prime. She was never classically beautiful, but imagination, intelligence confidence, charisma, and total concentration on her object of desire got the muse where she wanted to go.

The well researched book deep dives into every trip, residence, artwork, friend and associate. There

are things you might want to skim. Two thirds of Surreal concentrates on Gala and Dali with Dali overshadowing. We never glean the heroine’s feelings on her life and men. Neither she nor intimates are quoted about emotion or reason for behavior. Gala was clearly a force with which to be reckoned, but the woman herself eludes.

Opening: Gala wearing the Shoe Hat and Lips Jacket which she inspired. They were designed by Schiaparelli in collaboration with Dali in 1938. (Photo by Andre Caillet)

Photos not marked Public Domain are courtesy of the publisher.

Surreal – The Extraordinary Life of Gala Dali

Michèle Gerber Klein

Our editors love to read and independently recommend these books. As an Amazon Affiliate, Woman Around Town may receive a small commission from the sale of any book. Thank you for supporting Woman Around Town.